Resentment against hike in bus fare mounting in Bhopal

|

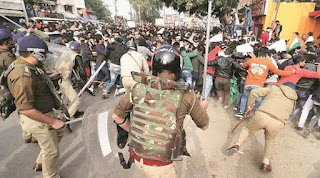

| Firozabad Riots |

According to reports, specific allegations have been registered about police excesses in Firozabad riots and the Criminal Investigation Department has been asked to investigate these. This step was taken after UP's Inspector General of Police had made an on-the-spot official inquiry.

Leaders of most political parties who visited Firozabad, including Congress's Subhadra Joshi, are said to have corroborated this viewpoint and blamed the Provincial Armed Canstabulary and the state police for having fanned the riots. Yet, to understand what happened in Firozabad, one has to understand life it is normally led in such small towns in Uttar Pradesh.

Most such towns subsist on some declining crafts and often make only an uneasy switchover to some other sluggish industry, Firozabad itself has a population of 1,33,534 according to the 1971 Census of these 40 per cent are Muslims and the rest Hindus.

The town is famous for its bangle industry. Its streets glitter with unfinished bangles In different stages of production; and its old crumbling buildings house furnaces around which children work in scorching temperatures. Originally, the craftsmen who are Muslims ran independent units. Now, after Partition and a series of riots in which their workshops were burnt down, they have taken to working for factory-owners who are mainly Hindus.

However, while these new factory-owners did transform the process of glass-smelting by bringing smelters and turners together in the factories, they did not centralise the whole process. Instead, they preferred to farm out some processes, like joining, cutting, and gilding. Consequently, a fragmented and dependent workforce continued to exist in the ghettoes, jealously guarding their communal identity and their craft which gave them their livelihood.

Nevertheless, the influx of industrial workers and the factories made inroads on the ancestral preserves of the craftsmen, giving them a feeling of insecurity. Even the workers' aristocracy, comprising some 200 highly skilled men earning over Rs 60 a day, is no longer exclusively Muslim.

Nor did the industrial influx bring general prosperity. There was no diversification. The bangle industry itself has been stagnant. Indeed, with the price of raw materials rising the factory-owners find it more profitable to sell their coal quota in the black at four times the purchase price, and at least 30 of the 80 factories in the town are mere fronts for resale of raw materials. Some factories are said to run for barely 15 days in a whole year.

Such being the economic environment, labour in the town is divided and insecure, often earning as little as Rs 2.60 a day. The situation is further complicated by the extensive use of child labour as a substitute for that of adults.

The physical conditions in which workers have to toil are appalling. Work in the midst of extremely high temperatures without adequate protection, has harsh effects. Tuberculosis is the main occupational disease and evidently a common one. Needless to say, neither adequate medical facilities nor insurance exist.

It was to such a town that the news of the Aligarh University Bill came. The craftsmen understand nothing of the university issue, and their children have little or no hope of ever getting there.

But their religious faith and affiliation are their sole anchor and, in the absence of a strong working-class movement, these remain the only cohesive force to which they can turn even to defend their livelihood. In the circumstances, the attack on the minority status of the university was viewed by them with alarm and seen as somehow a threat to themselves.

Once the Muslim craftsmen had responded defensively to the most diverse forces set in motion. For news, the instance, a bandh which was organised on June 16 was supported by Muslim traders and factory-owners for completely different reasons; at the same time, the stoppage was resented by the Hindu factory-owners. The Glass Industrial Syndicate declared the bandh 'communal' although the 400 posters that appeared were addressed to all communities.

At this juncture, too, the Hindu communal forces began to prepare to meet 'the challenge' by mobilising Hindus on a communal basis. All the four local branches of the RSS are said to have met and decided to teach the Muslims a good lesson "should anything happen during the bandh".

On the following day, on the initiative of the local Congress leader's son, young boys began to distribute yellow ribbons as against the black bands being worn by the Muslims. Clearly such a measure was bound to foster tension. Again, when a yellow pot was placed in the square in front of the Jama Masjid where a large crowd had assembled for prayer, it became clear that it was part of an attempt to create communal tension.

Nevertheless, there was peace till after the Friday prayer in the local Jama Masjid. Several thousand Muslims participated in that prayer, and thereafter except for a few hundred the rest dispersed quietly to their homes. Some elderly persons were seen urging even those that remained to go away.

But evidently there was a determined band of 50 or 60 boys and young men who were out to show their protest. Even so, they were persuaded to go quietly through the Hindu quarter; but once in the Muslim area, they started to shout slogans some of them apparently anti-national and against the Prime Minister.

Even then, in the absence of general tension or mass participation on either side, events could very well have been controlled at this stage if they had been handled tactfully.

But the police were heavy-handed and made a lathi-charge. The crowd took to stones. There was heavy brick- batting. It was at this point, reports have it, that one of the head constables took it upon himself to shoot. A boy in the crowd was killed.

The furious mob then raided the Eastern police station, where the head constable had taken refuge, and set fire to some furniture and other things they could lay their hands on. Thereafter, the police opened fire once again killing half a dozen or so Muslims on the spot. Curfew were imposed, and it was to continue for a full 87 hours.

But, meanwhile, a Hindu was stabbed. It is reported that the police carried him on a charpoy through the main market place, proclaiming that the Muslims had done this and heaping abuses on the Hindus of the area for having been 'cowards' and 'impotents'

Then followed a long and unrelieved night of terror. The police, with help from other quarters, seem to have let themselves go, shooting Muslims, plundering their homes, shops, and factories, making arrests on false and fabricated charges, manhandling and assaulting their women, and setting fire to their buildings. Even children were not spared.

The Town's tall, three-storeyed Jama Masjid, with its aged paralytic Imam in it, was set on fire. Islamia College, which catered to 60 per cent Hindu students, was completely destroyed, the whole building being burnt quite systematically. All this, while there was complete curfew in the town with orders to shoot at sight' and the PAC supposedly on guard at these buildings as elsewhere.

The curfew period, moreover, proved fertile ground for spreading rumours of all sorts. One such was that a score of Rajasthani Hindu labourers had been burnt alive in their huts. We were told that, in fact their huts were set on fire only on the following night and the next morning with the inmates being paid Rs 50 per family to move out.

We also saw victims of wanton violence: an old man shot through his shoulder; a girl with torn ear-lobes as she had had her ear-rings pulled off; a whole street where almost all the men bore marks of severe beatings even 10 days after the event. In fact, one man is reported to have died of the ill-treatment he received after his arrest.

Hindus, on the other hand, seemed to have suffered little or no loss. Even the Hindu goldsmiths living in Muslim areas were not harmed, while a few streets away Muslim shops were systematically looted and burnt.

The local Congress establishment seems to have given its support to these actions and even used the occasion to settle scores. The chairman of the municipality, a factory-owner himself, is reported to have accompanied a posse of policemen on a raid of his own workers living in Hajipura.

Witnesses reported that when he later went out as a member of the Peace Committee to distribute food to the victims, they refused it from him. The local MLA, a defector to the Congress, is also reported to have been involved. And some influential persons in the town, we were told, had opened free kitchens for the PAC and the police in three Hindu mohallas.

The administration, for its part, was responsible for giving semi-official currency to rumours such as that a transmitter had been discovered in the local. mosque. The telephone connections of Muslims are said to have been cut off for three to four days.

Even a short visit to the town, how- ever, confirms one thing: viz, that while the attack was on the minority community as a whole, it was directed with special vengeance at the craftsman and the worker. The former, especially in Ahmadnagar area, had their tools looted.

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY

AUGUST 19, 1972

Comments

Post a Comment

Thanks for your comment. It will be published shortly by the Editor.